The Jewish Ghetto in Venice, with its five precious synagogues embedded among multi-coloured buildings with numerous windows, is the most important and best conserved Jewish architectural and monumental complex in the world.

In this interview, Paolo Gnignati – Venetian civil law solicitor and  chairman of the Venice Jewish Community since December 2013 – reflects on the origin, the present and especially the future of the Ghetto, 500 years after its foundation.

chairman of the Venice Jewish Community since December 2013 – reflects on the origin, the present and especially the future of the Ghetto, 500 years after its foundation.

500 years ago Doge Leonardo Loredan signed the decree to found the Ghetto. What did this regulation mean to the Jews?

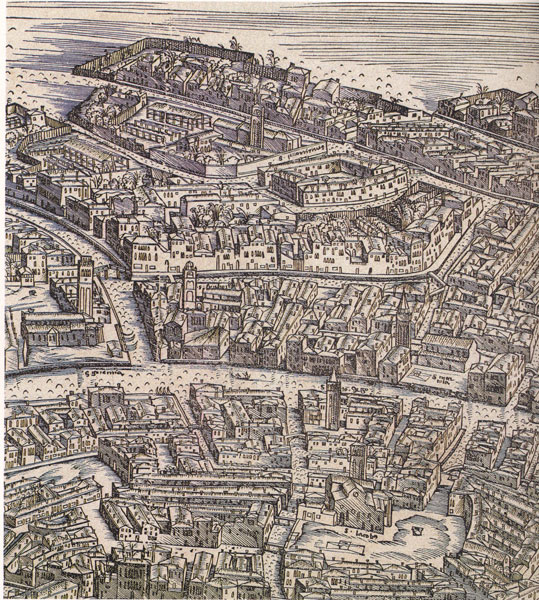

The foundation of the Venice Ghetto is marked by its high symbolic value in the history of Judaism. The term ‘ghetto’, a place name deriving from the already existing name of  the area in Venice where the ‘Jews’ enclosure’ was set up in 1516, was already being gradually used in the peninsula in the sixteenth century to designate the district in which the Jews were segregated. But regardless of the reason for which it was created – the segregation of the Jews – the Ghetto asserted itself, beyond any reasonable expectation, as a crossroads of European Judaism right from its foundation. A community of merchants but also of intellectuals and doctors who managed to make the place of segregation into a very lively cosmopolitan district in connection with Venice and all of Europe; a place where the houses had to be raised up to nine floors to make room for the thousands of Jews who flowed from East to West.

the area in Venice where the ‘Jews’ enclosure’ was set up in 1516, was already being gradually used in the peninsula in the sixteenth century to designate the district in which the Jews were segregated. But regardless of the reason for which it was created – the segregation of the Jews – the Ghetto asserted itself, beyond any reasonable expectation, as a crossroads of European Judaism right from its foundation. A community of merchants but also of intellectuals and doctors who managed to make the place of segregation into a very lively cosmopolitan district in connection with Venice and all of Europe; a place where the houses had to be raised up to nine floors to make room for the thousands of Jews who flowed from East to West.

By a fascinating paradox of history, the Ghetto has become a symbol of a high civic value

Alongside, printing presses flourished in Venice, such as that of the Giustiniani and the Bragadin, where important Jewish books were printed, but especially that of Daniel Bomberg, who published the first printed edition of the Talmud.

What is the role of the Jewish community in the conservation and protection of the Ghetto today?

The role of the Venice Jewish community, like any other, is primarily that of allowing Jews who live in its precincts to fully live their Jewish life. As the custodian of the immense heritage that the Ghetto represents, the community is then closely involved in the promotion of the Ghetto as a treasure chest and at the same time a formidable universal driving force of the most authentic Jewish culture and tradition.

The role of the Venice Jewish community, like any other, is primarily that of allowing Jews who live in its precincts to fully live their Jewish life. As the custodian of the immense heritage that the Ghetto represents, the community is then closely involved in the promotion of the Ghetto as a treasure chest and at the same time a formidable universal driving force of the most authentic Jewish culture and tradition.

How is the Jewish community inserted in the rich and complex context of an unusual city like Venice?

In the years of its greatest expansion, during the seventeenth century, a little more than 5000 Jews lived in the Ghetto. The Venice Jewish community now numbers about 450 members, few of whom still live in the Ghetto. The life of the community, apart from the religious needs of its members, also looks to the city and more and more often the Ghetto plays an important role as a meeting point and hinge between the various Venetian institutions.  The occasion of the 500th anniversary, with the inclusion of various institutional events at all levels in the programme, offers an unequivocal demonstration of this.

The occasion of the 500th anniversary, with the inclusion of various institutional events at all levels in the programme, offers an unequivocal demonstration of this.

What future role is there for the Ghetto in a city subject to the pressures of unchecked tourism?

The Ghetto is part of Venice and as such must be a resource for the city. It is now a vibrant and fascinating place in a strategic position, away from the main tourist routes and close to the most authentic and least contaminated parts of the city. It is not utopian to suggest that, thanks to its history and the special nature of Venice, place of cosmopolitanism par excellence, the Ghetto may in future become a centre of attraction for new generations of Jews from all over the world.

But the Ghetto is also a monument to pain and memory...

Keeping alive the memory of the crimes against the Jews and in particular the horrors of the Shoah is, and must remain, one of the absolute first missions of the Jewish community. But it is important to avoid positions withdrawn into the sole memory of the persecutions and to embrace a propositional vision in which the values of Judaism become active players in an epoch like ours in which intolerance and discrimination do not seem to go out of fashion. In a context of high migration pressure, violent attacks and fragile cultural identities, the history of the Italian Jewish community proposes a solid way towards integration; a road that does not mean renouncing specificity in favour of a myopic standardisation but, on the contrary, a careful highlighting of diversity. Because only from a protection of diversity can an authentic cultural pluralism take shape. The Venice Ghetto, because of a fascinating paradox of history, from being a symbolic place of segregation and discrimination becomes a powerful promoter at an international level of the values of freedom and tolerance.

***

Experiencing culture in the Ghetto

by Shaul Bassi

The 500th anniversary of the Venice Ghetto is an occasion for reflecting on a history that, starting from a time of segregation and from its creative reaction, has made the small but vibrant Jewish community of today an essential part of city life that, along with other associations, invigorates a rich series of artistic and cultural activities.

The 500th anniversary of the Venice Ghetto is an occasion for reflecting on a history that, starting from a time of segregation and from its creative reaction, has made the small but vibrant Jewish community of today an essential part of city life that, along with other associations, invigorates a rich series of artistic and cultural activities.

The Ghetto is now one of the liveliest and most international parts of the city, rich in artistic projects that mark it as a district projected towards the future and open to the world and not, as may be thought, closed in on itself and its own illustrious past. The most ambitious of these is the expansion of the Jewish Museum, which is destined to become more modern and interactive thanks to the work of Venetian Heritage. It already allows three synagogues to be visited and offers a look at the history of the Venetian Jews. Five centuries of history will in the meantime be recounted by the big exhibition Venice, the Jews and Europe, 1516-2016, which will  open in June at the Doge’s Palace, the very place where the decree was issued for the founding of the Ghetto.

open in June at the Doge’s Palace, the very place where the decree was issued for the founding of the Ghetto.

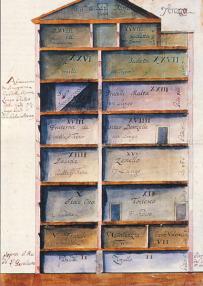

Two other projects are aimed specifically at emphasising the Ghetto’s role as an inspiration of new art and culture. With one foot in tradition and one in modernity, eight international artists were invited by the Beit Venezia - casa della cultura ebraica association to live in Venice for three weeks last autumn and study its fundamental role in the history of Jewish printing. Working in the stimulating workshops of the Scuola di Arte Grafica, the artists produced a new version of the Haggadah, the book the Jews read in the first evenings of the Jewish Passover (Pesach), celebrating their freedom from slavery, which by pure coincidence was taking place when the Ghetto was founded. Drawing inspiration from a historic edition printed in Venice in 1609, the artists produced 24 new illustrations that, after having been exhibited in the Jewish Museum, will be the basis of a modern edition of the book, which will symbolically take the Ghetto all around the world.

Then, over the last two years, various international writers of different backgrounds, languages and religions have been invited to ‘rewrite’ the Ghetto, and once again to live in the city and respond to their experience of the place with stories, essays and poetry. Amitav Ghosh, Daniel Mendelsohn, Nicole Krauss, David Albahari, Rita Dove and Igiaba Scego – aware that the name of this Venetian place has become a global metaphor – are already enriching the literary

Then, over the last two years, various international writers of different backgrounds, languages and religions have been invited to ‘rewrite’ the Ghetto, and once again to live in the city and respond to their experience of the place with stories, essays and poetry. Amitav Ghosh, Daniel Mendelsohn, Nicole Krauss, David Albahari, Rita Dove and Igiaba Scego – aware that the name of this Venetian place has become a global metaphor – are already enriching the literary

tradition on Venice with a new, important and very topical chapter that recognises how the problems that led to the creation of the Ghetto

– wars, migration, persecution and intolerance – are unfortunately still with us.