In the beautiful venue of Palazzo Canal, in the sestiere of Dorsoduro, during the 60th International Art Exhibition in Venice directed by Adriano Pedrosa, the Nigerian Pavilion presents Nigeria Imaginary, curated by Aindrea Emelife, Nigerian-British art historian at MOWAA in Benin City. The exhibition, which includes painting, photography, sculpture, installation, sound, film and augmented reality, fits right in with this year’s curatorial theme of a re-discovery and re-evaluation of those cultures considered subordinate to the Western ones.

The Nigerian pavilion is inspired by the Mbari Club founded in Ibadan in 1961, an Art Society that regarded this as a patriotic duty, interweaving myths, modernity and utopias. This spirit continues today with a new generation of artists promoting workshops of ideas and collective imaginaries. On the ground floor, the installation Pre-sky / Emit Light: Yes Like That by Precious Okoyomon welcomes visitors. It is a radio tower wrapped in a climbing plant that records atmospheric sounds and broadcasts voices of Nigerian artists. These artists answer philosophical questions posed by Okoyomon himself, creating a dreamlike and reflective experience. Moving up to the mezzanine, visitors are immersed in Onyeka Igwe’s film entitled No Archive Can Restore This Chorus of (Diasporic) Shame. The work explores the imprint left by the colonial films of the UK-run Nigerian Film Unit before independence. Igwe uses sounds from different cities to reinterpret and place these films in context, questioning the need to reclaim these spaces in order to end their continued exploitation. On the main floor, the site-specific work painted on the ceiling by Adeniyi-Jones, Celestial Gathering, interfaces with the Venetian architecture and recalls the influence of Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, while incorporating historical references from Nigerian art.

The Nigerian pavilion is inspired by the Mbari Club founded in Ibadan in 1961, an Art Society that regarded this as a patriotic duty, interweaving myths, modernity and utopias. This spirit continues today with a new generation of artists promoting workshops of ideas and collective imaginaries. On the ground floor, the installation Pre-sky / Emit Light: Yes Like That by Precious Okoyomon welcomes visitors. It is a radio tower wrapped in a climbing plant that records atmospheric sounds and broadcasts voices of Nigerian artists. These artists answer philosophical questions posed by Okoyomon himself, creating a dreamlike and reflective experience. Moving up to the mezzanine, visitors are immersed in Onyeka Igwe’s film entitled No Archive Can Restore This Chorus of (Diasporic) Shame. The work explores the imprint left by the colonial films of the UK-run Nigerian Film Unit before independence. Igwe uses sounds from different cities to reinterpret and place these films in context, questioning the need to reclaim these spaces in order to end their continued exploitation. On the main floor, the site-specific work painted on the ceiling by Adeniyi-Jones, Celestial Gathering, interfaces with the Venetian architecture and recalls the influence of Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, while incorporating historical references from Nigerian art.

In the front room, artist Ndidi Dike presents Blackhood: A Living Archive, consisting of 736 black wooden batons used as symbols of the victims of brutality, in the context of the #EndSARS movement demonstrations in Nigeria and the Black Lives Matter movement in the USA. Brown cards display the names of the people who have been killed, underlining the systemic injustice of police violence, which is counterbalanced by an attempt at global resistance. In the next room, Ndidi Dike presents Bearing Witness: Optimism In A Disquiet Present, the second chapter of the previous work. A triptych portrays a teenager next to totems with photographs of the #EndSARS demonstrations. Here the national mobilisation is captured as a crucial moment for the future of Nigeria, highlighting the youth’s desire for a united society and the key role of the next generation.

In the front room, artist Ndidi Dike presents Blackhood: A Living Archive, consisting of 736 black wooden batons used as symbols of the victims of brutality, in the context of the #EndSARS movement demonstrations in Nigeria and the Black Lives Matter movement in the USA. Brown cards display the names of the people who have been killed, underlining the systemic injustice of police violence, which is counterbalanced by an attempt at global resistance. In the next room, Ndidi Dike presents Bearing Witness: Optimism In A Disquiet Present, the second chapter of the previous work. A triptych portrays a teenager next to totems with photographs of the #EndSARS demonstrations. Here the national mobilisation is captured as a crucial moment for the future of Nigeria, highlighting the youth’s desire for a united society and the key role of the next generation.

In the opposite area to these rooms there is the space dedicated to the works of Toyin Ojih Odutola: five drawings made with pastel and charcoal on linen that uncover the Mbari house as a metaphorical and symbolic place. Odutola’s reflection explores an alternative narrative of the Nigerian country, seen through the eyes of those born in the colonial era. She tackles spirituality, tradition and history with different approaches, trying to access a collective cultural history that is in danger of being forgotten.

In the opposite area to these rooms there is the space dedicated to the works of Toyin Ojih Odutola: five drawings made with pastel and charcoal on linen that uncover the Mbari house as a metaphorical and symbolic place. Odutola’s reflection explores an alternative narrative of the Nigerian country, seen through the eyes of those born in the colonial era. She tackles spirituality, tradition and history with different approaches, trying to access a collective cultural history that is in danger of being forgotten.

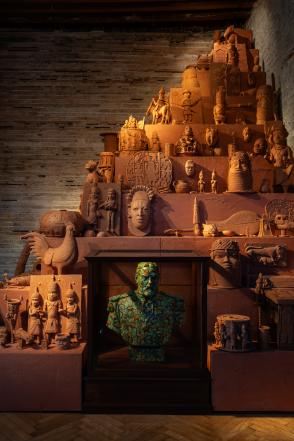

Finally, the work by Yinka Shonibare CBE RA, entitled Monument to the Restitution of the Mind And Soul, is impressive. Upon entering the room, one is immediately struck by the sight of an enormous pyramidal structure made of clay that houses reproductions, also in clay, of some artefacts that were victims of the great pillage in 1897 by the British colonists of Benin. With great irony, Shonibare depicts the bust of sir Harry Rawson, the principal of the operations, enclosing it in a case similar to those that today contain looted artefacts displayed in western museums. Reversing the crude colonial dynamics, Shonibare imagines an alternative future, where objects are recovered and boldly displayed: no longer ancient relics of a culture defined as "primitive", but symbols of artistic innovation belonging to Nigerian culture.

Finally, the work by Yinka Shonibare CBE RA, entitled Monument to the Restitution of the Mind And Soul, is impressive. Upon entering the room, one is immediately struck by the sight of an enormous pyramidal structure made of clay that houses reproductions, also in clay, of some artefacts that were victims of the great pillage in 1897 by the British colonists of Benin. With great irony, Shonibare depicts the bust of sir Harry Rawson, the principal of the operations, enclosing it in a case similar to those that today contain looted artefacts displayed in western museums. Reversing the crude colonial dynamics, Shonibare imagines an alternative future, where objects are recovered and boldly displayed: no longer ancient relics of a culture defined as "primitive", but symbols of artistic innovation belonging to Nigerian culture.

As proof of the importance of this initiative, the exhibition Nigeria Imaginary will be shown again as the opening exhibition in the new space dedicated to contemporary art at the MOWAA Creative Campus in Benin City.

As proof of the importance of this initiative, the exhibition Nigeria Imaginary will be shown again as the opening exhibition in the new space dedicated to contemporary art at the MOWAA Creative Campus in Benin City.