The paintings that adorn the room on the ground floor of the Scuola dei Santi Giorgio e Trifone do not tell a single story but develop a discontinuous narrative in nine scenes, drawn from a number of sources. While Christ praying in the Garden of Gethsemane and the Calling of Matthew are taken from the Gospels, the other canvases depict the story of Saint George and the dragon, that of the young Saint Tryphon the exorcist, the death of Saint Jerome and, finally, Saint Augustine in his study as he writes enlightened by the Holy Spirit.

Saint George – recently demoted from the list of certified saints admitted to worship by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith – is a figures who actually incorporate a large number of mythical, literary and moral figures and ideas, ultimately representing the personification of the virtuous hero, stronger than the seduction of the passions and their consequent dangers; in Eastern Christianity, moreover, he has also been adopted as a victorious defender against the infidels.

The lesser known and less revered Tryphon is a child dedicated to liberating from evil, especially when it takes up residence in innocent (?) young girls, as in the case depicted here (in a weak composition of uncertain attribution) in which the ‘beast’ has attacked no less than the daughter of Emperor Gordian.

The lesser known and less revered Tryphon is a child dedicated to liberating from evil, especially when it takes up residence in innocent (?) young girls, as in the case depicted here (in a weak composition of uncertain attribution) in which the ‘beast’ has attacked no less than the daughter of Emperor Gordian.

The story of Saint George, as represented by Vittore Carpaccio, is depicted with all the characteristics of a courtly tale but is worth reading with care, as it is accompanied by a complex system of symbolic and allegorical references with roots in the moralised culture of the medieval world. Not that this detracts from  the immediacy and charm of the splendid scenes: quite the contrary.

the immediacy and charm of the splendid scenes: quite the contrary.

The young and handsome knight breaks into the scene of a tragic tale: the citizens of the Libyan city of Selene are forced to appease the voracity of a monster that emerges daily from a nearby lake. At first two sheep a day are enough but the herds are scarce and soon it is necessary to sacrifice a young boy or girl drawn by lot until, one day, it is the turn of the king’s daughter to be exposed to the fury of the monster. While she resignedly awaits her destiny, the blond warrior appears: without a helmet, ‘without fear and beyond reproach’, he seems to have just emerged from the skilled hands of a great coiffeur, with his fashionably curled blond hair, as he rides an elegant black mount.

The battlefield is scattered with the remains of those who suffered before Giorgio’s arrival: fragments of bones, mummified skulls, mangled bodies, reptiles feeding on them. This sort of showcase of horrors is therefore a moral scene.

Carpaccio was a cultured and humanist painter, and nothing appears by chance in his paintings. Painted in the first decade of the sixteenth century, the canvases in the Scuola dalmata are among the finest of his production, although not all of them attain the level of quality of the St. George and the dragon. The second scene has less verve and dynamism, but the details are fabulous: robes and turbans (how many times we have cited Proust and Albertine’s dressing gowns upon looking at Carpaccio’s cloaks!), architecture and dogs, plants and harnesses, parrots and lizards, boots and drums, beards and rugs...

Apart from the Orientalist setting with palm trees and exotic details of various kinds, the two scenes relating to Saint Jerome are very different and, indeed, the events take place in Bethlehem. The presence of the saint is soon explained: the great intellectual was a native of the Roman town of Stridon (where this was is unclear, but certainly it was near the border between Roman Dalmatia and Pannonia; one contender is Stridone – now Zrenj – in Istria) so his presence in the Venetian school of the Dalmatians is fully justified.

Jerome brings a mild-mannered lion to his monastery, a beast not only meek in behaviour but also wounded in a leg, like in the famous fable of Androcles (narrated by Aulus Gellius) and as in other moralistic and educational tales in the manner of Aesop. Old Jerome – traditionally depicted as a penitent in the desert or at work in his studio – reacts almost like a child finding an abandoned kitten on the street and taking it lion home. His arrival causes a predictable reaction that is depicted in masterful manner by Carpaccio: the fleeing monks draw a sort of musical score, or the choreography of a ballet that spreads from the foreground to the rear, eventually involving all the spaces of the community.

Everything returns to calm in the scene showing the saint’s funeral. Reduced to a skeleton, consumed by age and work, exhausted by his intellectual strivings: what remains of Girolamo has already almost descended into the flags of the cemetery; for sure he is already earth, already dust, marking the boundary between time and eternity, between history and faith. All around, softly, the untiring ora et labora of the monastery goes on.

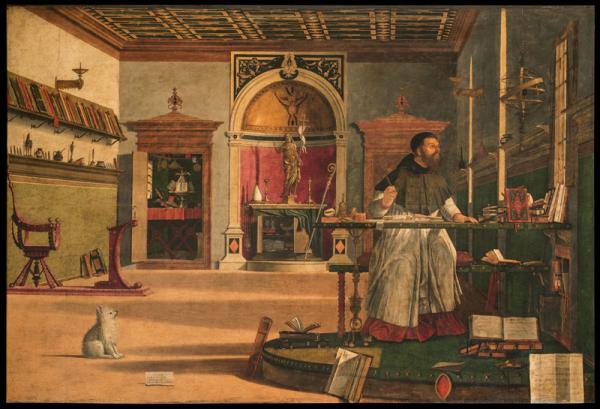

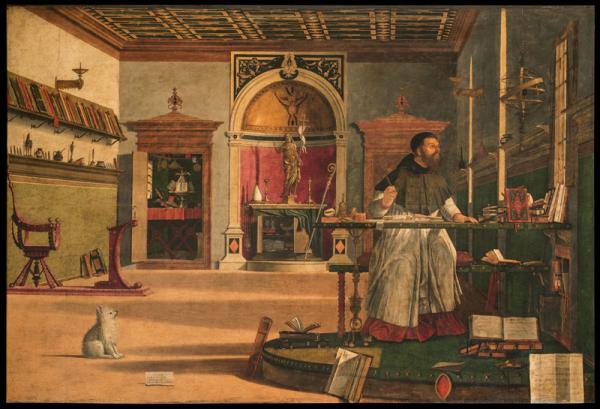

And here is the last canvas of the Scuola. In it we see a scholar seated in his elegant study. It has all the paraphernalia of the great intellectual, of the desk researcher: a bookcase with codices and books studied and left lying open, writing materials, a large armillary sphere, astrolabes, an hourglass, seals, lamps, items of naturalistic interest. At the bottom, however, are the signs of his status: the pastoral, the miter, liturgical furnishings, candelabra, the nacelle for incense, the ampullae for the celebration of the Eucharistic sacrifice. Above all there is the altar in the niche in the centre with a bronze of Christ in triumph and, beneath the liturgical vestments, some missals. In the middle of the room, there is a chair with a wooden and leather back and a kneeling stool. He is clearly a bishop, as his own garments confirm.

He is writing and looking at a fixed point inside the light that comes from the window to his left. The atmosphere is perfect and magical. The space is determined millimetrically by the golden light and by the shadows drawn on the floor: a whole universe of objects forms a refined and crowded Wunderkammer – a sort of quintessence of totalising and orderly knowledge, a logical and theological, physical and metaphysical, divine and human, scriptural and philosophical summa. Everything is founded on the invisible line that leads the scholar’s gaze out from this space, into the light that illuminates the scene both in metaphorical and real terms.

He is writing and looking at a fixed point inside the light that comes from the window to his left. The atmosphere is perfect and magical. The space is determined millimetrically by the golden light and by the shadows drawn on the floor: a whole universe of objects forms a refined and crowded Wunderkammer – a sort of quintessence of totalising and orderly knowledge, a logical and theological, physical and metaphysical, divine and human, scriptural and philosophical summa. Everything is founded on the invisible line that leads the scholar’s gaze out from this space, into the light that illuminates the scene both in metaphorical and real terms.

The figure portrayed is Saint Augustine, as we know for sure today thanks to a study by Helen I. Roberts and to the clarifications of Augusto Gentili. An Augustine who was associated with Saint Jerome through a series of interpretative misunderstandings, and acute mediations, scriptural apocrypha and historical coincidences, the ins and outs of which have been felicitously reconstructed and interpreted. This enables us to return to the lands of Istria and Dalmatia, and refrain from drawing subdivisions and boundaries between the various ethnic and geographical components of that splendid nearby land that lies just across the sea.

The saint’s white dog observes, silently and composedly, the labours of men.

Bio: Giandomenico Romanelli is an art historian and curator. For a long time he was director of the Musei Civici di Venezia.

***

An Heritage made of Art and Values

On 24 March 1451, about 200 Dalmatians gathered in assembly to appoint the heads of the Dalmatian Brotherhood, a necessary step for the republic’s Council of Ten’s official recognition of the Scuola Dalmata dei Santi Giorgio e Trifone, also known as the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni.

Through the foundation of the School, the Dalmatians – who were increasingly numerous in Venice or who visited often for cultural or work reasons – became an integral part of the social fabric of the city.

While it is true that the original citizens of Dalmatia saw the Scuola as the place of the Dalmatian nation in Venice – where they could meet for both professional and religious and spiritual reasons – it is equally true that the cultural, political and economic ties between Dalmatia and the Serenissima made the Dalmatians in Venice as proud of their origins as they get bound to their new homeland.

In like manner to the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, the Scuola Dalmata dei Santi Giorgio e Trifone survived the suppression of monasteries and schools ordered by Napoleon in 1806 unscathed, thus managing to preserve both its function and its extraordinary artistic heritage, of which the Carpaccio cycle described in this article is the most famous work.

Today the cultural value of the School is enriched by the precious Archive-Museum of Dalmatia. The only cultural reference point for Dalmatians in Italy, it contains numerous documents and memorabilia donated by Dalmatian exiles. In this way the Scuola continues its valuable work of promoting its extraordinary artistic heritage and of spreading the values and traditions it has been embodying for 569 years.

Useful information for a visit

Castello 3259/a

Opening times

Mon / lun 1.30 pm-5.30 pm

Tue to Sat / mar a sab 9.30am-5.30pm

Sun / dom 9.30 am-1.30 pm

Contacts

+39 041 5228828

scuoladalmatavenezia.com