What would the myth of Venice be without the voice of John Ruskin? His were those passionate words that with great effectiveness described the beauty, decay and magnificence of the Gothic buildings and the “rudderless drifting” of the  Renaissance ones, in line with his very decidedly anti-classical vision; a vision that truly made his a voice that stood out from the crowd in those years, and which even today bears witness to his role as the first true guardian of ancient Venice, of that little he still found intact and which now, thanks to him, remains.

Renaissance ones, in line with his very decidedly anti-classical vision; a vision that truly made his a voice that stood out from the crowd in those years, and which even today bears witness to his role as the first true guardian of ancient Venice, of that little he still found intact and which now, thanks to him, remains.

The John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice exhibition that we wished to entrust to the capable hands of one of the greatest Italian art historians, Anna Ottani Cavina, arose from a desire to give at least a partial answer to this question. It is an exhibition which, despite being almost the first that Italy has devoted to this versatile English intellectual, has primarily focused on his personal development as artist, a side that is not as well known as his thinking expressed in the thousands of pages penned during the course of his life and published at the time in magnificent editions. These, to give just some examples, include Modern Painters, a treatise of rules for the good painter mixed with a highly singular history of art, Praeterita, his personal diary, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, comprising his essay dedicated to the precepts of good construction, and Sesame and Lilies, a bold book for the time, which introduced principles of equality between men and women.

thinking expressed in the thousands of pages penned during the course of his life and published at the time in magnificent editions. These, to give just some examples, include Modern Painters, a treatise of rules for the good painter mixed with a highly singular history of art, Praeterita, his personal diary, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, comprising his essay dedicated to the precepts of good construction, and Sesame and Lilies, a bold book for the time, which introduced principles of equality between men and women.

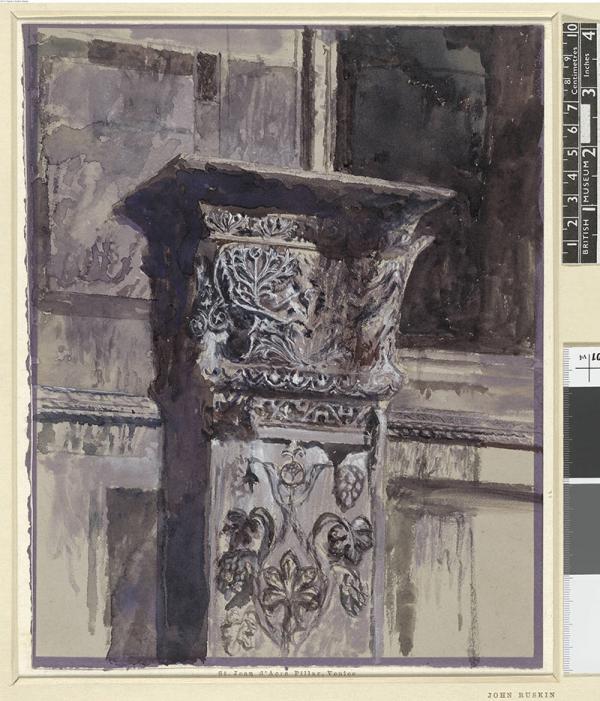

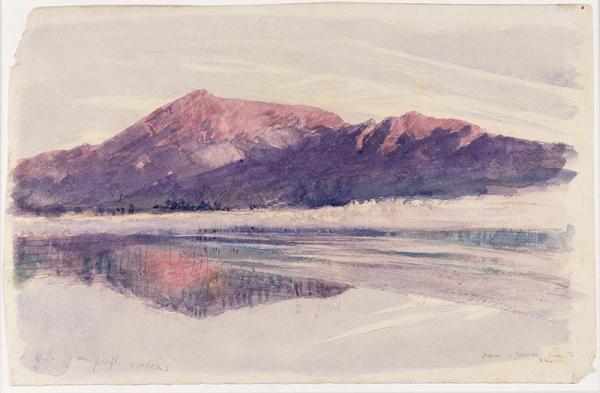

His work as an inspired painter—he was a refined watercolourist of landscapes, skies, clouds and many beloved architectural features—is imbued with the leitmotif of his complex and sophisticated critical thinking, which for Venice marked a milestone (and the first desperate appeal) in a battle, one that at the time was certainly neither easy nor popular: the protection of that ancient art and that “vital and non-formal” architecture that he identified with the Gothic style, from decay, negligence and the first bad restorations. All this was threatened with oblivion, first of all because of what he himself called the “Renaissance evil” and then, at the time of his eleven stays in the lagoon, because of the indifference and  ignorance of his contemporaries, ready to do away with the last ancient remains.

ignorance of his contemporaries, ready to do away with the last ancient remains.

A survey of Ruskin’s monumental literary and critical work, which is today more than ever precious to us for the reasons described above, could not therefore overlook his personal interests as a painter and scholar of the phenomena of nature, which he explored with rigorously scientific method even when he did so for pleasure, taking advantage of his two particular talents, drawing and writing. The first was the result of an innate and well-cultivated attitude concerning the use of all figurative techniques: pen, burin, watercolour, oils and more. And he was highly distinguished in the second from his early years, for his great analytical skill and close attention to detail, for his  ability to “photograph” with extraordinary interpretive acuteness (and well before the use of the daguerreotype became a help and a habit for him) the “living” forms of all those landscapes, those monuments, those aspects of nature and those expressions of human creativity that were the object of his tireless striving after knowledge in the most disparate fields, from geology to botany, art criticism to architecture, literature to the first probings of the newborn social sciences.

ability to “photograph” with extraordinary interpretive acuteness (and well before the use of the daguerreotype became a help and a habit for him) the “living” forms of all those landscapes, those monuments, those aspects of nature and those expressions of human creativity that were the object of his tireless striving after knowledge in the most disparate fields, from geology to botany, art criticism to architecture, literature to the first probings of the newborn social sciences.

The text is an excerpt from the introduction to the exhibition catalogue.