This retrospective – about ninety works –

duly acknowledges Tancredi. What part did

he play in the renewal of the arts in Italy,

and more, between the 1950s and 1960s?

Tancredi  was always an ‘other’ painter. He was never part of the group in which everyone tried to place him, the Informal. He did not change the history of art of the 1950s and ’60s. He actually surpassed it. A ‘world-beater’, who had all the tools of the new painting.

was always an ‘other’ painter. He was never part of the group in which everyone tried to place him, the Informal. He did not change the history of art of the 1950s and ’60s. He actually surpassed it. A ‘world-beater’, who had all the tools of the new painting.

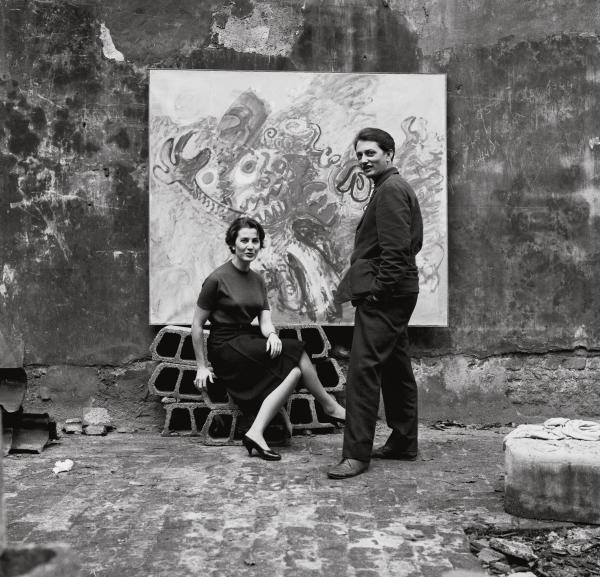

Peggy Guggenheim and Tancredi met in

1951. Tancredi was twenty-four and had just

come back from Rome. He had seen some

of Peggy’s contemporary art collection at the

1948 Venice Biennale: Kandinsky, Mondrian,

Pollock etc. She let him use a studio in her

museum house on the Grand Canal. How did

that period affect his development?

His first solo exhibition was in 1949. Presenting it, he wrote that his painting ‘is intended to experience a problem’. Venice was a big workshop to him. The 1948 Biennale was the ‘book’ in which he studied. Peggy Gugenheim immediately guessed his potential and made him a contract: ‘an exception’, wrote Peggy, as for Pollock before him and no one else.  She thus endorsed Tancredi on the international painting scene very early.

She thus endorsed Tancredi on the international painting scene very early.

Tancredi Parmeggiani was born in Feltre in

1927. He was eight when he lost his father. His

artistic training was precocious. What role did

his Venetian meetings play, long before that

with Peggy Guggenheim?

Although very young, Tancredi was already, according to declarations, a person with his charge of poetry and desperation. They

were years of rich exchanges with the Venetian cultural scene. It was the city of Vedova,

the – political par excellence – painter of black and white. Tancredi was at first the antithesis of this with his painting of air, of coloured dots and of joyful inconsistency.

Tancredi and cities, the places of his life.

He had an ambivalent relationship with

Venice: he owed it a lot, but outside there

were others, vast lands.

The city was to him an affective place,

to be breathed. It is not only architecture; it is the dust of its atmospheres. Tancredi painted the vapours and reflections of Venice, the splendour of its mosaics, the brown of the dusks. He did not feel that Milan and Paris were entirely his. Venice was his world and he missed it, but Milan and Paris were places for updates, comparisons, even if bitter and contradictory, with modernity, with the market. Travelling was no less indispensable to him than returning.  Tancredi sought the creative short-circuit: Venice was a stock of imagination, Milan and Paris the social dimension, the meeting of a young man – he died at the age of thirty-seven – with other young people, who like him really thought they could change things.

Tancredi sought the creative short-circuit: Venice was a stock of imagination, Milan and Paris the social dimension, the meeting of a young man – he died at the age of thirty-seven – with other young people, who like him really thought they could change things.

An endless production is attributed to him.

‘Thousands’ of works, wrote Dino Buzzati,

remembering him in 1967, three years after his suicide, in the Corriere della Sera.

Tancredi never stopped painting and especially drawing. He did so continuously, even for whole days. He was almost compulsive in tracing his ‘stenographs’: the myth of the artist who dies young, who has produced a lot, almost portending his premature end.

‘My weapon against the atom bomb is a blade

of grass.’ The Hiroshima triptych represents

a change, a realisation. Buzzati, who came

from the same Veneto mountains as Tancredi,

called the prophetic monsters that at a certain

point began to populate his paintings ‘hopping, crooked larva’.

The blade of grass is the rebellion of beauty to balance terror. It is the time of objection and disappointment. The savagery of the  Algerian War had a very painful impact on Tancredi: the France of the Revolution, which denied human rights, which did not give up the colonial empire. He said of the ghosts

Algerian War had a very painful impact on Tancredi: the France of the Revolution, which denied human rights, which did not give up the colonial empire. He said of the ghosts

he painted: ‘I find them in the street’.

Buzzati asked in that ‘funeral speech’ if

Trancredi was ‘a great painter, destined to have his name in bold type in the History

of Art. He certainly cannot be considered the

leader of a school. A romantic figure, yes’.

Half a century later, who is Tancredi?

He is a ‘famous unknown painter’, because in its compositional freshness Tancredi’s

work is alive, but dismembered and scattered, spread as it is mainly in private collections.

It is always and only an exhibition that gives him back to us and each time it is a revelation.

Rome, the city of the dramatic end. The painter’s body was found on 1 October 1964 in the

waters of the Tiber. Tancredi had left the following words in his notes: ‘Life is still entirely to be discovered’.

As is Tancredi… and I think this is his fate.