LA FONDAZIONE GIORGIO CINI was founded in 1951 by Vittorio Cini, in memory of his son Giorgio, with the aim of restoring the island of San Giorgio Maggiore and making it into an international centre of cultural activities. The foundation now has rich art collections and a precious wealth of books. It presents exhibitions that explore the connections between past and present, organises conferences and is a vibrant study and research centre. One of the projects now under way, ‘Le Stanze del Vetro’, held with the Swiss Pentagram foundation, promotes the study and appreciation of twentieth-century and contemporary art glass.

We met Luca Massimo Barbero, director of the foundation’s Istituto di Storia dell’Arte, and David Landau, founder of Pentagram Stiftung, to tell us about these projects.

***

Interview with Luca Massimo Barbero, curator, art critic, director of the Fondazione Cini’s Istituto di storia dell’arte.

What role should a private cultural institute have?

Encouraging cultural studies, being fertile ground for exchanges relating to knowledge, in this case the history of art, with an approach that is both international and local. This institute’s most important tasks include, precisely, research, archiving and publication activities, whose hub is the Fondazione Giorgio Cini, through its library and photo library, and the  place intended to receive researchers from all over the world, the Centro Vittore Branca.

place intended to receive researchers from all over the world, the Centro Vittore Branca.

How do you interpret your role as artistic director/curator?

The artistic curator takes to the director that for which he was initially trained, the love of archives and of study. The history of art is facing a time of development and change and this advance in research can, at times, make use of exhibitions, which I think must be specialised and accessible in order to engage the experts and a wider audience in the study of our artistic, archive and book wealth.

What relationship does the Fondazione Cini intend having with Venice?What contribution can it make in producing culture in a city that wants to be a world vanguard, not just a world stage?

The Fondazione Cini is a living part of the city of Venice, it is one of its throbbing cells. It studies not only its past but also its current cultural criticalities, stylistic originalities and artistic continuities. The institute, with the whole foundation, has managed to restore its links with the heart of Venice by reopening the Palazzo Cini to the public.  This is a place that is becoming a kind of radar for making known the riches of the island of San Giorgio Maggiore, which, while maintaining its character as a place of study, is also able to offer itself as an exhibition venue.

This is a place that is becoming a kind of radar for making known the riches of the island of San Giorgio Maggiore, which, while maintaining its character as a place of study, is also able to offer itself as an exhibition venue.

In what ways can you imagine working with the other cultural institutions, the school, the university?

There are established links with the city’s institutions, such as the programme promoted through the Branca scholarships, which are offered not only to the international study centres but also the local universities. In this period we are also working on the Museum Mile project, which connects the Gallerie dell’Accademia, the Collezione Guggenheim  and the Punta della Dogana exhibition spaces to the Galleria di Palazzo Cini.

and the Punta della Dogana exhibition spaces to the Galleria di Palazzo Cini.

Three years after the start of the ‘Le Stanze del Vetro’ project, what response has this long-term programme for studying and recovering a glorious tradition had?

I think that the hub of the ‘Le Stanze del Vetro’ activities, like their documentary basis, which is the Centro Studi del Vetro, lies in the constant search for high quality study and in the broad chronological spectrum proposed.

‘The Fondazione Cini

is one of Venice’s throbbing cells.’

Luca Massimo Barbero

The ten-year project is intended not only to focus on Murano production, its great designers and craftsmen, but also to have a more international scope, becoming an exhibition model. It is no mere chance that various exhibitions held at San Giorgio have been requested by other institutions, from the Metropolitan Museum of New York to the MAK in Vienna.

What place do the Cini’s ancient collections have in the foundation’s cultural project?

One of my first wishes was to return the Vittorio Cini collection to the public; which we have  highlighted with the publication of a new gallery catalogue. Palazzo Cini is now becoming the place in which to present our collections to the public, conserved in that which, traditionally and symbolically, is called the Sala del tesoro.

highlighted with the publication of a new gallery catalogue. Palazzo Cini is now becoming the place in which to present our collections to the public, conserved in that which, traditionally and symbolically, is called the Sala del tesoro.

Such is the case with the exhibition that will open on 19 September on the Fondazione Cini’s eighteenth-century Veneto drawings, with a special loan: Francesco Guardi’s Capriccio from the Jacquemart-André Museum.

***

Interview with David Landau, art historian and entrepreneur, collector of twentieth-century venetian glass and founder, with his wife marie-rose kahane, of Pentagram Stiftung.

A project like ‘Le Stanze del Vetro’ helps reawaken the proud awareness of a history. Is rediscovery enough for restarting?

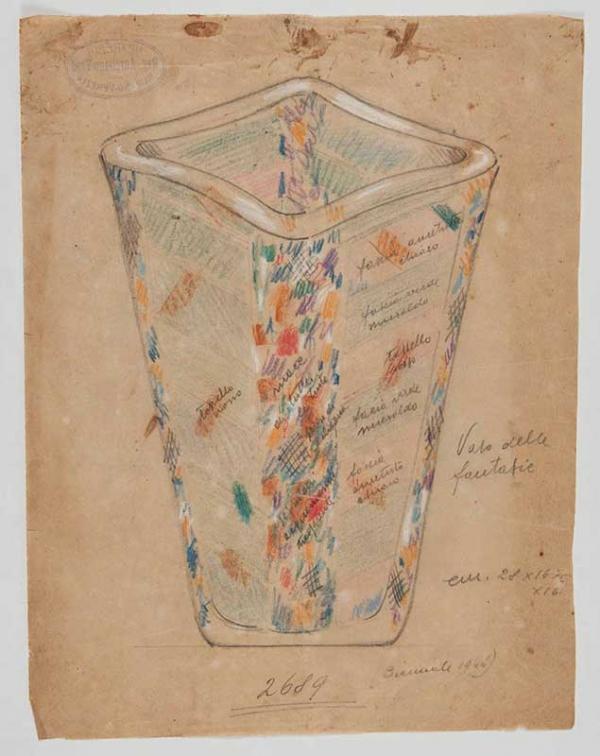

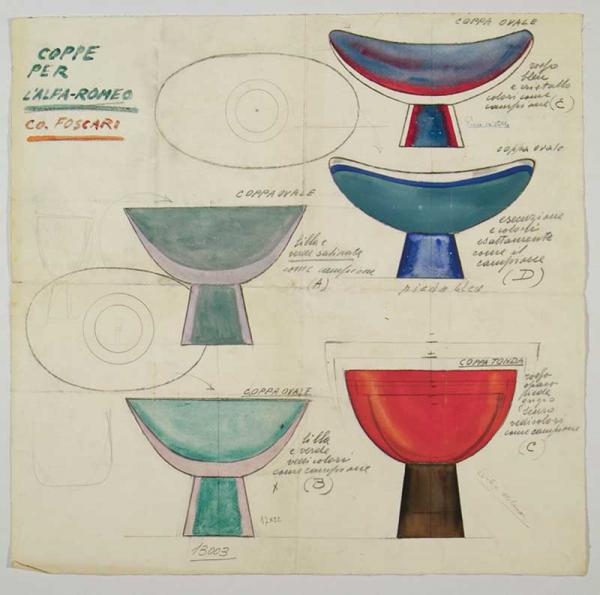

No, it isn’t, but it helps. The project was conceived to record and show, not only the world, but the people of Murano themselves, the amount of extraordinary work produced in the last 100 years and to point out that the rush to quantity rather than quality, typical of these decades, has been a serious error. The aim is to arouse curiosity, reawaken the pride of a community and stimulate new creativity by means of studying archive documents, the account of what was done in the first 80 or 90 years of the last century, and the display of masterpieces that emerged from the hands of skilled master craftsmen. And the story of the Venini glass works, which we want to reconstruct, along with others, can be raised to being a paradigm of a period that marked an epochal change in the revival of the art of Venetian glass in the twentieth century.

‘Le Stanze del Vetro’ opened in 2012 with Carlo Scarpa, brilliant architect, designer and artistic director at Venini (1932-1947). Is the fertility of that creative drive still possible?

It’s always possible. Murano has a millennial history, marked by highs and lows, from periods of crisis and recovery to peaks of absolute excellence. The secret to succeeding again is understanding one’s own  time, opening up to the world, offering the more attentive clients not the repetition of old-dated models, but the essence of one’s own identity. In this Carlo Scarpa was a master and an emblem. Choosing a name of such international renown and quality to open the project was a guarantee of success. Indeed, the exhibition then moved to the Metropolitan Museum of New York, drawing record numbers – 100,000 – and once again attracting attention to Murano as entity and label.

time, opening up to the world, offering the more attentive clients not the repetition of old-dated models, but the essence of one’s own identity. In this Carlo Scarpa was a master and an emblem. Choosing a name of such international renown and quality to open the project was a guarantee of success. Indeed, the exhibition then moved to the Metropolitan Museum of New York, drawing record numbers – 100,000 – and once again attracting attention to Murano as entity and label.

Three years after it began, what response has this study and recovery programme had?

To finally see university students in Venice taking an interest in the subject is one of the greatest satisfactions. Consider that since the 1940s only thirty-two theses have been written on it. But since the start of the exhibitions there have been many requests for information on the materials held by the Centro Studi del Vetro, set up in the context of our project. Involving the new generations is one of the challenges and the meetings organised between master glass makers and students, and the workshops for families with children go in this direction.

How important is it to keep international comparison open for a new development of glass art in Venice?

Looking beyond one’s own confines is vital and stimulating for the growth of any production system, and experimentation must be constantly nourished. The exhibition just finished on Glass from Finland in the Bischofberger Collection is the manifesto of a nation that sought its place in the world and has built its own contemporary identity through design. After Fulvio Bianconi at Venini the programme will continue with Il Vetro degli Architetti of the Viennese Secession: Olbrich, Hoffmann, Loos…; in 2017 it will be the turn of works by Ettore Sottsass, in the centenary of his birth, to then continue with the contemporary glass in the Cirva collection in Marseilles.

will be the turn of works by Ettore Sottsass, in the centenary of his birth, to then continue with the contemporary glass in the Cirva collection in Marseilles.

‘In glass I look for absolute beauty.’

David Landau

How did your great love of glass and in particular that of Venice begin?

It grew out of my great love for my wife. When we met she owned a collection of Venini glass, a few pieces, but marvellous. They are still among the best we have. I thus started to get to know the art of glass and I have never stopped appreciating it and buying it: from twenty pieces we now have 1500.

What beauty do you look for in the glass pieces you own?

The same as that I look for in paintings, in nature, in my children... absolute beauty.