May you live in interesting times: is it a joke or a threat? What Ralf Rugoff has explained, regarding the choice of this maxim as the title for the Biennale he has curated is that it is not an ancient Chinese saying but something much more recent: the phrase, which underlines the difficulties inherent in any moment of transition, has been used by figures ranging from Sir Austen Chamberlain to Albert Camus, Robert Kennedy and Hillary Clinton. There is no trace of it in Chinese treatises. Rugoff knows that every self-respecting curator must start from a strong assertion, set out a range of problems on the table and renew the conceptual structure of the exhibition.

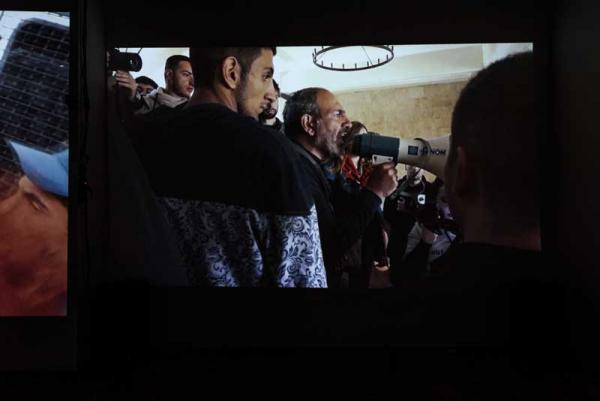

The latest edition of the International Art Exhibition was born under the sign of fake news and it establishes a dialogue with it, understood as the need to manipulate and modify stories so that they can become legends, things to tell or, to return to present-day language, create a storytelling able to convince. However, if in times of postmodern thought one might think that truth was always only an opinion, in these times of voluntary manipulation of information it is necessary to recognise that facts exist. Even though it be necessary to know how to see things from many points of view, if only to maintain a flexible viewpoint: rules that are too rigid, especially those dictated by fear of the ‘other’ and of change, tend to compress intelligence.

An approach like this introduces us to the levels of complexity that the exhibition has tried to tackle: on the one hand, there is the world of the ‘always on’ and 24/7 internet, which has upset our circadian rhythms and globalised our world –  including the inner one – to the point of making us doubt values that we believed to be certain (and this is a source of the burn-out we feel affects us so often). On the other hand there is something atavistic: a way of being men that does not change and that contemplates inventing, hypothesising, fantasising, imagining. A fake, in fact, is not the opposite of a something real, but the result of a process of a conception that shares something with narration. No living being needs continuous narratives except for man, who even after childhood never loses the ability to simulate for fun – but often a very serious game – a struggle, an expectation, the search for a prey to love or to feed on. In the twentieth century, visual works of art have changed form, technique and secondary functions – they are no longer necessarily either depictions or decorations – but they have maintained that which is the core of their need to

including the inner one – to the point of making us doubt values that we believed to be certain (and this is a source of the burn-out we feel affects us so often). On the other hand there is something atavistic: a way of being men that does not change and that contemplates inventing, hypothesising, fantasising, imagining. A fake, in fact, is not the opposite of a something real, but the result of a process of a conception that shares something with narration. No living being needs continuous narratives except for man, who even after childhood never loses the ability to simulate for fun – but often a very serious game – a struggle, an expectation, the search for a prey to love or to feed on. In the twentieth century, visual works of art have changed form, technique and secondary functions – they are no longer necessarily either depictions or decorations – but they have maintained that which is the core of their need to exist: they are stories that are evoked through various means, from performance to painting, from film to virtual reality, but all unified by their inclination not to repeat the world as it is. Indeed, even a ready-made contains a part of simulation, because by changing context, every sign changes meaning. Man needs to live in a continuous state of ‘storydoing’, of building new meaning.

exist: they are stories that are evoked through various means, from performance to painting, from film to virtual reality, but all unified by their inclination not to repeat the world as it is. Indeed, even a ready-made contains a part of simulation, because by changing context, every sign changes meaning. Man needs to live in a continuous state of ‘storydoing’, of building new meaning.

Any evolved animal, to tell the truth, grows up playing, that is, simulating adventures that put it on the alert: a cat thinks of playing with the prey while grabbing at a ball, a dog follows and brings back a stick as if it were game. Mammals all have an extreme need to imagine, and above all to imagine difficult conditions, in which their ability to overcome the obstacle is fielded and tested.  This is why the idea of difficulty comes together to combine with that of play, as Rugoff himself underlined in statements such as: “It is when we play that we are more fully human”. Playing also and above all means communicating, imagining hypothetical worlds as cubs do, remembering that “the meaning of works of art does not reside so much in the objects as in the conversations – first between the artist and the work of art, then between the work of art and the public, and then between different audiences”.

This is why the idea of difficulty comes together to combine with that of play, as Rugoff himself underlined in statements such as: “It is when we play that we are more fully human”. Playing also and above all means communicating, imagining hypothetical worlds as cubs do, remembering that “the meaning of works of art does not reside so much in the objects as in the conversations – first between the artist and the work of art, then between the work of art and the public, and then between different audiences”.

Rugoff has therefore proposed a title that has a basic meaning, which alludes to the world in turmoil in which we find ourselves living, but it also has some other aspects, such as the use of good and bad lies, the need for narration, the conviction, finally, that art can give answers with respect to historical emergences and from which it cannot be said to be free.  Not art pour l’art, therefore, no Aventine for a world that could nevertheless feel itself blessed to live in a state of luxury. The artist must anyway pay attention to the questions of the present and give his own answer. Knowing that things will not change, probably, but taking up the challenge of proposing works that are exempla for common action.

Not art pour l’art, therefore, no Aventine for a world that could nevertheless feel itself blessed to live in a state of luxury. The artist must anyway pay attention to the questions of the present and give his own answer. Knowing that things will not change, probably, but taking up the challenge of proposing works that are exempla for common action.

Angela Vettese is an art historian, curator and director of the Master’s degree course in Visual Arts and Fashion at the Department of Culture of the Iuav University of Venice. She has been president of the Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa (2002-2013), director of the Galleria Civica di Modena (2005-2008), director of the Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro of Milan (2008-2010), president of the jury of the Venice Biennale (2009) and artistic director of Artefiera of Bologna (2016-2018).