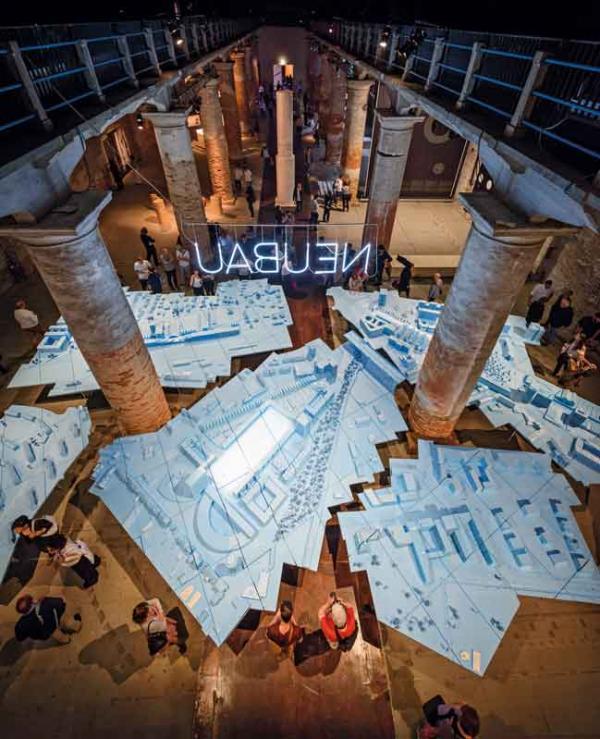

‘Venice is an unsurpassable architecture lesson for us all: it is inhabiting the impossible’. Alongside Alejandro Aravena, Paulo Mendes da Rocha clutches his career Golden Lion and grasps the universal significance of Venice, that which makes such an ancient city perhaps the most projected of all towards the future. This Architecture Biennale would also like to inhabit the impossible: it brings news from the lacerated and vibrant peripheries of the world, like the South America of Mendes da Rocha, Brazilian, and Aravena, Chilean.

the future. This Architecture Biennale would also like to inhabit the impossible: it brings news from the lacerated and vibrant peripheries of the world, like the South America of Mendes da Rocha, Brazilian, and Aravena, Chilean.

The Silver Lion at the eleventh Biennale in 2008 for his Elemental studio’s social architecture projects, now, at the age of 49, having just been awarded the Pritzker Prize, the architects’ Nobel, Alejandro Aravena is directing that sensitivity towards ‘his’ exhibition.

Reporting from the front: the title of this Biennale seems an appeal to a militant architecture. What answers have come from the front?

It is first of all important to listen, to focus the questions.  They are the right questions for orienting projects, for suggesting pertinent responses. Let’s take immigration: a new problem in terms of proportion and speed of means is met with outdated schemas. We should not be surprised at the anger and anxiety, the insecurity and resentment they generate.

They are the right questions for orienting projects, for suggesting pertinent responses. Let’s take immigration: a new problem in terms of proportion and speed of means is met with outdated schemas. We should not be surprised at the anger and anxiety, the insecurity and resentment they generate.

Where does the front line run?

The forms of places can improve or ruin people’s lives. If architecture must conceive functional solutions for the individual and the common good, then the most ruinous front cannot but pass through the congested megalopolises, the squalor of the suburbs, the carnage, the waste of land and materials, pollution, conflicts, environmental disasters and natural catastrophes.

The good projects come up against great resistance: the avidity and impatience of capital or the obtuseness and conservatism of bureaucracy tend to reproduce banal, mediocre, monotonous environments. This is the first line from which we want news, sharing successes or exemplary cases, in which architecture has been able to and can make the difference.

In Italy you have measured the architecture of Greek Sicily and of the Renaissance. How have they influenced your education?

Every discipline has a nucleus of knowledge. In the case of architecture this consists of the buildings themselves. They are lessons in the field. Redrawing them is like redesigning them. But it is only when you measure them that you find yourself before the decisions that the person who conceived them took. Designing is preferring and someone has chosen best. Getting direct experience of them is exhilarating, it conveys faith and at the same time humility; attitudes that are absorbed nourishing oneself on the body of knowledge of the past.

The name Elemental is the manifesto of what idea of architecture?

When, by dint of subtracting, you have reached the elementary level, you can no longer remove anything else from a thing without overturning its essence.  In many parts of the world you are forced to work like this. The scarcity of means trains you to imagine essential solutions, defending an irreducible line of quality. It is worth being prepared, because this will increasingly be the future. On the other hand, the abundance of resources at times leads to the opposite risk, that of a scarcity of meaning in some architecture.

In many parts of the world you are forced to work like this. The scarcity of means trains you to imagine essential solutions, defending an irreducible line of quality. It is worth being prepared, because this will increasingly be the future. On the other hand, the abundance of resources at times leads to the opposite risk, that of a scarcity of meaning in some architecture.

The Pritzker Prize medal carries the ‘commandments’ of the Roman architect Vitruvius: durability, convenience and beauty. Venerated and betrayed?

The Vitruvian triad condenses the irrevocable conditions of architecture. The challenge is to integrate them and it is no mere chance that they evoke a triangle, the first geometrical figure with which you can build something stable. Two sides alone would not be enough, four could be redundant.

Is Venice just a stage or is it the ‘impossible’ city, which contemporary ones should strive to resemble?

It is now also the conviction of many economists that competitiveness will more and more be played out not so much on the cost of goods and services, nor on that of transport, but on the creation of knowledge. You may be able to call on the most advanced technology, but it is still the face to face meeting that stimulates it more than anything. The creatives choose the cities that offer a better quality of life and Venice offers an ideal context, which elsewhere would have to be built artificially: being able to still meet walking down the street. The cities of the future must as far as possible make these creators of knowledge able to recognise one another.

not so much on the cost of goods and services, nor on that of transport, but on the creation of knowledge. You may be able to call on the most advanced technology, but it is still the face to face meeting that stimulates it more than anything. The creatives choose the cities that offer a better quality of life and Venice offers an ideal context, which elsewhere would have to be built artificially: being able to still meet walking down the street. The cities of the future must as far as possible make these creators of knowledge able to recognise one another.

With what state of mind should one visit this Biennale?

Without preconceived ideas. If you don’t come here ‘empty’ – as empty as the Chilean desert of Atacama on the 2016 Architecture Biennale poster – you will miss the chance to fill yourself with a new world.