Talking about Chagall is not easy, because in a way he is self-sufficient. He lived for a long time, painted a great deal, and experienced the most significant and often dramatic upheavals of the twentieth century. He was close to numerous artistic movements: Symbolism, for instance, which is touched upon in the first section of the exhibition, and he had Surrealist companions in adventure and exile, such as Max Ernst, shown in section 3, and friends among the German Expressionists, the French Fauves and Constructivists, as emerges in Rabbi No. 2 at Ca’ Pesaro. However, he did not really adhere to any artistic current. He developed and pursued a language all his own, mixed with the avant-garde and with the primitivism he had learnt in his youth in Paris and used, like Symbolism, to convey the sense of his own world, his own dream.

Talking about Chagall is not easy, because in a way he is self-sufficient. He lived for a long time, painted a great deal, and experienced the most significant and often dramatic upheavals of the twentieth century. He was close to numerous artistic movements: Symbolism, for instance, which is touched upon in the first section of the exhibition, and he had Surrealist companions in adventure and exile, such as Max Ernst, shown in section 3, and friends among the German Expressionists, the French Fauves and Constructivists, as emerges in Rabbi No. 2 at Ca’ Pesaro. However, he did not really adhere to any artistic current. He developed and pursued a language all his own, mixed with the avant-garde and with the primitivism he had learnt in his youth in Paris and used, like Symbolism, to convey the sense of his own world, his own dream.

If what distinguishes Chagall is the idea of the expressive freedom of imagination and creative fantasy, the leitmotif of this journey into the colour of dreams becomes a narrative made with Chagall as the tutelary deity in each section. Twelve works by Chagall are on display, including three paintings that are absolute masterpieces: The Rabbi, The Lovers, exceptionally on loan from the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, and Vitebsk. Village Scene from Vienna, from the collections of the Albertina. Together with these are exhibited drawings, tempera works and etchings accompanied by the priceless original plates that Chagall engraved to create the Bible series, on loan from the Marc Chagall National Museum in Nice.

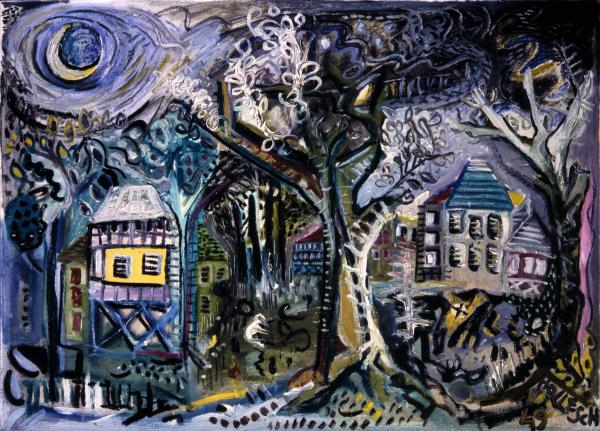

A universe made of dreams and memory takes material form in Chagall’s depictions of the Jewish village of his childhood, Vitebsk, a subject that the artist explored again and again in numerous works throughout his life, as an ideal place, a place of the soul. “Mine alone / Is the country in my soul”: Chagall’s dreamworld often includes Vitebsk, wandering Jews, the face of his father, a Chassidim Jew, and animals and his uncle playing the violin. Animals flying or playing instruments, floating carts, wandering Jews and beggars on rooftops: Chagall’s entire imaginative universe is substantiated by the memory of Vitebsk and his childhood.

A central section deals with perhaps the most powerful feeling of the human being, love, while the theme of the spiritual, the unfathomable yearning for the search for the Divine, underlies Chagall’s entire training and production and is examined in the exhibition in a large section. The religiously themed works range from the series of prints dedicated to the Bible, with the engravings exhibited alongside the original plates, to the theme of the Crucifixion, which Chagall, who was Jewish, approached with interest and sensitivity, at times representing the drama of Jewish persecution through the image of Christ on the Cross. On display alongside his own work are a number of artists from the Civic Collections of Ca’ Pesaro who have explored the theme of religion from different points of view, such as the Finnish Veikko Aaltona, the extraordinary Frank Brangwyn, the Hungarian mystic Istvan Csok and the very young Nicolò De Mio, winner in the Video Art category of the Artefici del Nostro Tempo Competition in 2022, who is present in the Gallery’s collections. Another presence is Garbari, a ‘Capesarino’ artist of the first generation and a skilful ‘engraver’ of primitive figures on a black slate sky, is exhibited alongside Lynn Chadwick and her winged figures, crucified but also angelic, poetic but also symbols of architecture devastated by the bombings of World War II.

A central section deals with perhaps the most powerful feeling of the human being, love, while the theme of the spiritual, the unfathomable yearning for the search for the Divine, underlies Chagall’s entire training and production and is examined in the exhibition in a large section. The religiously themed works range from the series of prints dedicated to the Bible, with the engravings exhibited alongside the original plates, to the theme of the Crucifixion, which Chagall, who was Jewish, approached with interest and sensitivity, at times representing the drama of Jewish persecution through the image of Christ on the Cross. On display alongside his own work are a number of artists from the Civic Collections of Ca’ Pesaro who have explored the theme of religion from different points of view, such as the Finnish Veikko Aaltona, the extraordinary Frank Brangwyn, the Hungarian mystic Istvan Csok and the very young Nicolò De Mio, winner in the Video Art category of the Artefici del Nostro Tempo Competition in 2022, who is present in the Gallery’s collections. Another presence is Garbari, a ‘Capesarino’ artist of the first generation and a skilful ‘engraver’ of primitive figures on a black slate sky, is exhibited alongside Lynn Chadwick and her winged figures, crucified but also angelic, poetic but also symbols of architecture devastated by the bombings of World War II.

Finally, in the last room of the exhibition, where the lapis lazuli blue of the first sections, taken from the headgear of the Rabbi of Ca’ Pesaro, becomes lighter, the archetypes of fairy tales explode on the scene. Here, the artist’s powerful creative imagination is once again expressed to the full. La Fontaine’s Fables, which we all know as an archetype and as oral tales, provide further nourishment for Chagall’s fantasy world. He explored a world of myth that is evident too in the works of Félicien Rops and Frank Barwig, but also in an unprecedented and surprising Pan by Claudio Parmiggiani, in the splendid graphic work of Corrado Balest, in the surreal fantasy of George Grosz and Carlo Hoellesch, and finally in the small miniature in the seventeenth-century manner immersed in the magic of a fable-like everyday life by Marta Naturale.

Finally, in the last room of the exhibition, where the lapis lazuli blue of the first sections, taken from the headgear of the Rabbi of Ca’ Pesaro, becomes lighter, the archetypes of fairy tales explode on the scene. Here, the artist’s powerful creative imagination is once again expressed to the full. La Fontaine’s Fables, which we all know as an archetype and as oral tales, provide further nourishment for Chagall’s fantasy world. He explored a world of myth that is evident too in the works of Félicien Rops and Frank Barwig, but also in an unprecedented and surprising Pan by Claudio Parmiggiani, in the splendid graphic work of Corrado Balest, in the surreal fantasy of George Grosz and Carlo Hoellesch, and finally in the small miniature in the seventeenth-century manner immersed in the magic of a fable-like everyday life by Marta Naturale.

I hope that the exhibition will once again show how Chagall was a great artist and also a dreamer in the best sense of the word; an optimist, despite the difficulties he had to face during his long life. The message that I hope emerges is one of humility, imagination, the power of the dream, the possibility of discovering the divine also through feeling. Chagall’s message is, I believe, that there is no need to understand and rationally translate everything, because one’s own truth can also be reached through dream and memory.