“In invention there is none to match messer Andrea Mantegna, who is indeed most excellent…, but Giovanni Bellino is excellent in his use of colour.”

Venice, 16 July 1504. In this letter to Isabella d’Este, Marchesa of Mantua, for whom he used to procure works of art, the writer, Lorenzo da Pavia, a maker of musical instruments, pinpoints the difference between the two artists.

The compositional approach of the two Presentation at the Temple is the same. One wonders whether the two brother-in-law painters ever brought the two paintings together.

This is the first time – in modern times, at least – that Mantegna’s tempera on canvas, which arrives from the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, and the oil on panel by Bellini, which instead belongs to the Fondazione Querini Stampalia in Venice, have met up. They are being shown together at Palazzo Querini, and will then appear at the National Gallery in London, and finally at the Gemäldegalerie.

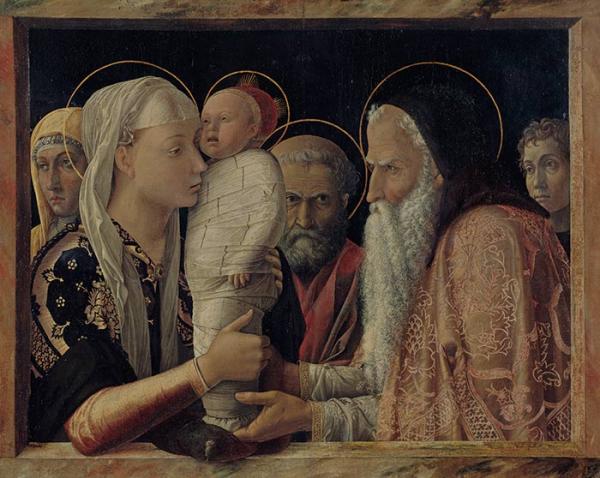

The composition must have been conceived in the Paduan workshop of Mantegna. His Presentation probably precedes the other by at least a decade. Andrea married Nicolosia, Giovanni’s sister, shortly before, in 1453. It seems to be the two of them, Mantegna and his wife, who are depicted at the sides of the composition, framing the scene. Perhaps it was an awaited or newborn child to have inspired the artist: a sort of record on canvas to ensure good luck in a state of mind common to all parents, a mixture of confidence and trepidation. Mary, as a most human Mother, seems reluctant to separate herself from the Child, as though resisting the fulfilment of Christ’s tragic and glorious destiny, which Simeon revealed in the Gospel of Luke: “this child is set for the fall and rising again of many in Israel…Yea, a sword shall pierce through thy own soul also”. The swaddling bands around Jesus are those of a newborn child, but they also evoke the Cross and burial. Joseph gazes at the prophet with a troubled and serious expression. He is present in the background, but centrally placed: and this is the part he played in the story of Salvation, that of a silent custodian.

The Venetian version by Giovanni Bellini stretches to make room for two other figures on the side. The Presentation by Mantegna is a powerful 4/3 proportion, while that of Bellini is a cinematographic 16/9. Opinion has it that the older woman may be Giovanni's stepmother or his wife, while the man may be a self-portrait of the artist next to his brother-in-law Andrea.

This family “photo”– a little more crowded than Mantegna’s –seems a tribute of affection around the Holy Family.

In his style, Giovanni is clearly different to Andrea. Mantegna encloses the event within a hefty marble frame. Aureoles, beards and precious fabrics have a calligraphic refinement that is still Gothic in feel. The colours contrast, and the cushion juts out of the painting. At the end of the fifteenth century, Ulisse Aleotti wrote of Mantegna, declaring that he “sculpted in paint”.

The reinterpretation by Bellini is polished by the light in a wide range of reds. The frame has disappeared. Only a stone parapet remains. In this way the black background expands and the group stands out against it, gaining in enigmatic abstractness, in modernity.

The reinterpretation by Bellini is polished by the light in a wide range of reds. The frame has disappeared. Only a stone parapet remains. In this way the black background expands and the group stands out against it, gaining in enigmatic abstractness, in modernity.

The panel is first noted in the inventory of Querini Stampalia in 1809.

The exhibition is hosted in the rooms of the sixteenth-century palazzo and is both a compelling dialogue between two Renaissance masters and a discovery or rediscovery of the treasures of the Fondazione, established in 1869 through the bequest of the last Querini, Giovanni, to “promote a devotion to fine studies and useful disciplines”. It is preparing to celebrate its 150th anniversary with its art collections, the furnishings of the museum house, the library, and the architectural additions designed over the last fifty years by Carlo Scarpa, Valeriano Pastor and Mario Botta.

The Querini’s Presentation is now universally attributed to Giovanni Bellini but two centuries ago, when it entered the collections, it was listed as being a work by Andrea Mantegna.

The solidity of the composition is certainly attributable to Mantegna but Bellini re-invented it, combining a classical composure with that impelling desire for experimentation that would drive him throughout his life.

Albrecht Dürer met him during his two stays in Venice. In Italy, the German artist sought a direct experience of the latest in compositions and colour.

In 1505, when Bellini was in his seventies and full of admiration, Dürer wrote: “He is very old, but he is still the greatest”.

His painting is contemporarily antique, like the Fondazione Querini Stampalia.