The first unabridged edition of Giacomo Casanova’s Histoire de ma vie faithful to the original manuscript was published in 1960 by the German F.A. Brockhaus publishing house in collaboration with Plon, a Parisian bookshop. It took more than 150 years after the death of the famous adventurer in 1798 in Dux, (Duchcov, in present-day Czechia), before the original text contained in the precious papers was finally published. The manuscript – written in French, as was customary in eighteenth-century Europe – had reached the publisher Brockhaus in 1821, sold for 200 thalers by Casanova’s nephew-in-law, Carlo Angiolini, and remained stored in a safe until 1960, when it was made available to scholars for the first time. In the same year, the Italian Casanovist Piero Chiara translated the memoirs into Italian for Mondadori, and this translation also served for the subsequent edition in the Meridiani series. In fact, countless editions of Histoire de ma vie saw the light of day from the early nineteenth century. The first one in German, published between 1825 and 1829, offered a heavily edited version with omissions and variations from the original text. All subsequent French-language editions were invariably purged of parts considered excessively libertine for the morals of the time, as well as characterised by profound stylistic interventions.

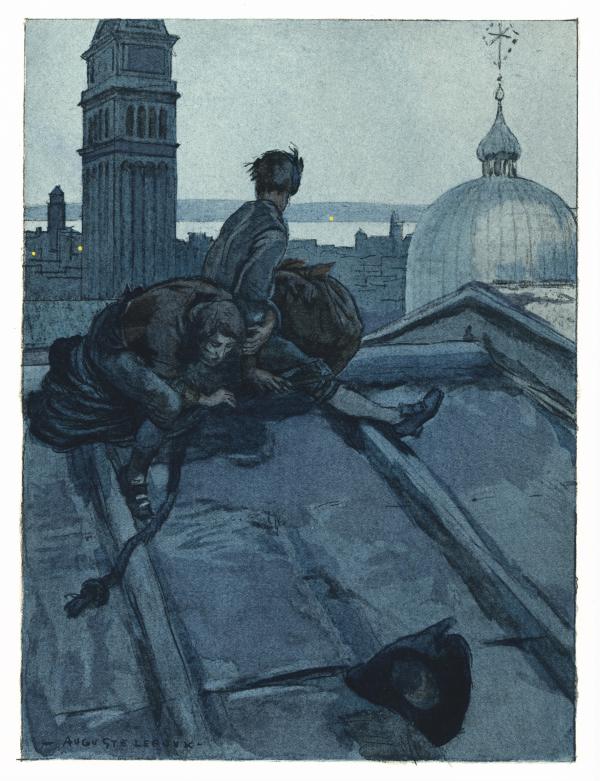

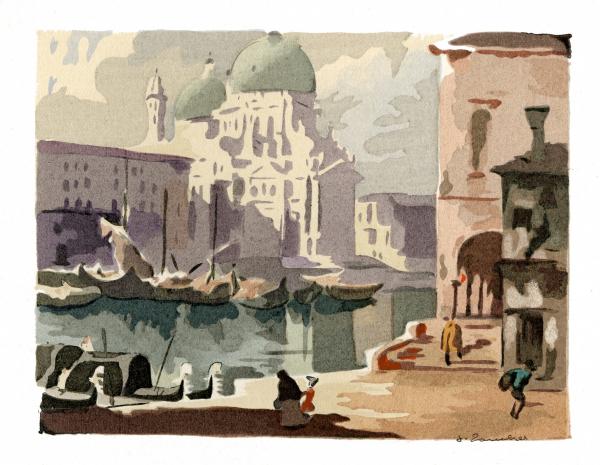

It was France above all that celebrated Casanova with editions also of great aesthetic quality and refined illustrations, in the wake of the great tradition of the illustrated (and erotic) book that was all the rage during the first decades of the twentieth century. These included eye-catching editions illustrated by Auguste Leroux, Umberto Brunelleschi, Jacques Touchet and George Barbier, to name but a few. For the extraordinary quality of the images, it is worth mentioning Une aventure d’amour à Venise illustrated by the Danish painter Gerda Wegener, known for having married the first transsexual person in history, an affair recounted in the celebrated 2015 film The Danish Girl. These numerous and sometimes splendid editions contributed substantially to the creation of the myth of the libertine Casanova. A myth that fitted perfectly with the strongly Romantic vision of Venice characteristic of the European imagination of the time.

It was France above all that celebrated Casanova with editions also of great aesthetic quality and refined illustrations, in the wake of the great tradition of the illustrated (and erotic) book that was all the rage during the first decades of the twentieth century. These included eye-catching editions illustrated by Auguste Leroux, Umberto Brunelleschi, Jacques Touchet and George Barbier, to name but a few. For the extraordinary quality of the images, it is worth mentioning Une aventure d’amour à Venise illustrated by the Danish painter Gerda Wegener, known for having married the first transsexual person in history, an affair recounted in the celebrated 2015 film The Danish Girl. These numerous and sometimes splendid editions contributed substantially to the creation of the myth of the libertine Casanova. A myth that fitted perfectly with the strongly Romantic vision of Venice characteristic of the European imagination of the time.

Giacomo Casanova’s notoriety was such that he became an archetype of debauchery and adventure, making him the most famous Venetian in the world after Marco Polo. The price of this notoriety, however, was very high: the oblivion of Casanova’s true personality. His high cultural profile, philosophy, brilliant intelligence and the extraordinary literary quality of his memoirs were crushed by the myth of the amorous adventures. On some occasions, the paternity of the manuscript was even questioned, with some attributing it to Stendhal, claiming that certainly a character like Casanova could not have written such a masterpiece. Scores of ‘Casanovaphiles’ gathered in various associations have gone to great lengths over the last century to make the world aware of who Giacomo Casanova really was. But for the general public, thanks in part to some comic film adaptations (and I am certainly not referring to the masterpiece that is Federico Fellini’s Casanova) he has continued to remain imprisoned in his character as seducer.

In 2010, the Brockhaus publishing house sold the manuscript of the memoirs to the Bibliothèque Nationale de France for more than seven million euros. It was the occasion of a major exhibition but, above all, of a new critical edition edited by Gérard Lahouati and Marie-Françoise Luna for Gallimard. It is interesting to note that the same publishing house had previously published the manipulated text. The French acquisition of the manuscript contrasts with the deafening silence of Italian institutions – especially the Biblioteca Marciana – which remains a vivid testimony to the failure of the city of his birth to recognise Casanova’s greatness, and in a certain sense certifies his status as a post-mortem exile.

In 2010, the Brockhaus publishing house sold the manuscript of the memoirs to the Bibliothèque Nationale de France for more than seven million euros. It was the occasion of a major exhibition but, above all, of a new critical edition edited by Gérard Lahouati and Marie-Françoise Luna for Gallimard. It is interesting to note that the same publishing house had previously published the manipulated text. The French acquisition of the manuscript contrasts with the deafening silence of Italian institutions – especially the Biblioteca Marciana – which remains a vivid testimony to the failure of the city of his birth to recognise Casanova’s greatness, and in a certain sense certifies his status as a post-mortem exile.

This year we celebrate the tercentenary of Giacomo Casanova’s birth. The best way to honour his memory will be to read or reread his works or, at least, that little masterpiece that is Histoire de ma fuite des prisons de la République de Venise qu’on appelle les Plombs. L’Histoire de ma vie remains an extremely gripping, at times formidable work, and probably the most extraordinary account of eighteenth-century European society ever written.